Travis County Primary Candidates Jockey to Champion Criminal Justice Change

A closer look at the heated District Attorney, County Attorney, and County Court at Law races

By Michael King, Fri., Feb. 7, 2020

Unscrew the locks from the doors!

Unscrew the doors themselves from their jambs!

Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass

Everybody supports "criminal justice reform." Advocates across the entire political spectrum trumpet their support for reducing, redesigning, or replacing America's "carceral state." On the right, it takes the form of calls for increasing public safety while cutting costs, insisting on "personal responsibility" instead of social context, while finding cheaper means of imprisonment or surveillance. On the left, the range of proposals is broader: exchanging rehabilitation for retribution, reducing arrests and imprisonment for nonviolent offenses (especially drug possession), promoting restorative justice, etc. ... shading into "wraparound social service" solutions rather than only prosecution and prison.

Ask Travis County Democratic primary candidates and voters what they mean when they advocate "criminal justice reform," and you'll receive a range of answers. They can be as extensive as the "13-Point Plan" proposed by County Attorney candidate Laurie Eiserloh: Her list runs from better prosecutorial intake procedures through reduced enforcement of minor offenses to establishment of a mental health center, to more efficient uses of technology. A simpler definition was suggested by a layman, Austin Firefighters Association President Bob Nicks. "To me, criminal justice reform means not devoting our law enforcement resources to minor, nonviolent crime – but focusing those scarce resources on serious crime, especially violent crime."

Especially in the judicial and prosecutorial campaigns, candidates highlight their remarks with "criminal justice reform," running the gamut from Nicks' simple formula to Eiserloh's more elaborate breakdown. The most common specific reforms are two: eliminating the cash bail system that discriminates against poor defendants, and moving resources away from nonviolent crimes (particularly drug crimes) toward more aggressively prosecuting violent crimes: murder, rape, assaults – especially sexual assaults.

There are three related Democratic primary campaigns in which these ideas are most prominent: District Attorney, County Attorney, and County Court at Law No. 4 judge. In one way or another, the 10 Democratic candidates among those three races are expressly committed to "criminal justice reform." In theory at least, there shouldn't be much to argue about, except who is perhaps truly the best "reformer." In reality, there's plenty of argument – even some bitterness – throughout the campaigns, and considering the three of them together can provide a fuller sense of what Travis County officials mean when they brandish the term "reform."

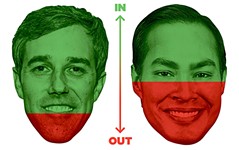

Failures of Communication: The District Attorney Race

Most rancorous of the three campaigns is that for Travis County District Attorney, where incumbent Margaret Moore faces aggressive challenges from Workers Defense Project co-director José Garza and attorney Erin Martinson. Moore has a lengthy record as a prosecutor (in various offices) and two stints as an (appointed) county commissioner, and was elected in 2016 in the wake of the organizational disarray that followed predecessor Rosemary Lehmberg's drunk-driving arrest and prosecution. She campaigned as a "reformer" and points to a series of accomplishments in that vein: reorganizing the office and dismissing some prosecutors judged subpar performers (thereby generating some backlash); reducing to misdemeanors (from state jail felonies) the vast majority of low-level drug and theft prosecutions; increasing prosecutions and convictions for sexual assault and family violence; acting to reduce racially discriminatory impacts of the system; and creating specialized units – adult sexual assault, family violence, and notably a Civil Rights Unit to address discriminatory prosecutions (and to review all police-involved shootings).

Her opponents each insist that all of this is too little, too late. Garza's strongest advocacy is for radical reform or elimination of the cash bail system that is keeping some pretrial inmates in the Travis County Jail who can't afford their court-assigned bond. Martinson was recruited to run by advocates who condemn the D.A.'s handling of rape/sexual assault cases, and while she joins Garza in supporting bail reform, her harshest criticisms are of what she says is negligence in the treatment of sexual assault victims.

"They [the prosecutors] don't care about the victims," Martinson told the Chronicle, "and I know that because they come to me [as an advocate] and say they aren't listened to and get no communication." Despite the rising prosecution numbers, Martinson says the situation has actually gotten worse during Moore's three-year tenure. (Her charges are reinforced by the federal lawsuits filed against the D.A. by some victims. Moore – and County Attorney David Escamilla – says she can't respond substantively while the litigation is pending.)

Moore answers her opponents by reiterating the actual progress the office has made, and says they willfully underestimate the complexities of programmatic changes in the criminal justice system. On cash bail, she notes that while judges actually assign bonds, the county has in place a "robust" personal bond (release on recognizance) system that releases more than 70% of those arrested, and is pursuing ways of increasing that number. (Garza gives that percentage a "C-" grade, measured against a few jurisdictions elsewhere whose percentages are higher.) Moore counters that there are reasons other than poverty that keep some pretrial inmates in jail, including the level of offense, multiple charges, and other factors. On sexual assault, Moore cites the growing numbers (more than 200) of prosecutions since 2017 (135 guilty pleas and trials), and also notes that she was rebuilding that process after it was derailed by the headline failures of the Austin Police Department's DNA lab.

"We can't just fix these things by the D.A. issuing a memo to the judges," Moore says, "unless you want the response to be just the judges rolling their eyes." She argues that local law enforcement requires extensive collaboration among several different agencies – courts, police, prosecutors (felony and misdemeanor), and Commissioners Court – and that every incremental step requires research, outreach, consensus (and funding).

Moore's opponents respond that the D.A. is offering insufficient excuses for not moving more quickly. "It's always somebody else's fault that these reforms aren't taking place," says Garza. He and Martinson point to the 2017 breakdown of collaboration between local sexual assault advocacy groups and the law enforcement representatives as evidence that Moore can't handle public criticism; she responds that collaboration is impossible in an atmosphere of relentless accusation (and subsequent lawsuits).

Whose Experience Counts? The County Attorney Race

In the County Attorney race, the current debate hasn't been as vitriolic, and (thus far) hasn't turned as decisively on the subject of criminal justice reform as has the D.A. race. Instead, the most consistent thread has been which candidate is most precisely qualified to succeed retiring incumbent Escamilla and therefore to pursue the range of reforms that (everybody agrees) need action. The debate also conforms to the specific demands of the office – responsibility for misdemeanor prosecutions rather than felonies, as well as Travis County's representation in civil matters.

The candidates represent quite a range of experience: former Judge (and Assistant County Attorney) Mike Denton; current Assistant C.A. Laurie Eiserloh (who's also worked for the state and city); Austin Mayor Pro Tem Delia Garza (former city firefighter and assistant attorney general); and criminal defense attorney Dominic Selvera. All are committed to reforms now reflexive in criminal justice discussions: decarceration, bail reform, reduced emphasis on nonviolent crimes (especially low-level drug offenses), more proactive prosecution of domestic violence (with better social services), expanded diversion courts, and so on.

Selvera, a Democratic Socialist, is campaigning generally to the left of the others; his default policy positions include complete abolition of cash bail and the "Portuguese model" of drug reform. The latter would mean decriminalization of all drugs (not just marijuana), and treating all drug use solely as a public health question (either treatment or simply no harm/no action; he acknowledges that would require major changes in state and federal law).

The other three candidates each point to documented records of reform. Eiserloh has been a prominent defender of gay rights throughout her legal career, beginning with her days as executive director of the state Lesbian and Gay Rights Lobby (now Equality Texas); she cites her work with the city of Austin to achieve domestic partner benefits and her legal fight against anti-gay legislation and the anti-immigrant Senate Bill 4. Garza also promotes the City Council's opposition to SB 4, while citing her own policy work to reduce racial discrimination, decriminalize homelessness (more generally, poverty), and to increase budget support of social services (a useful skill before Commissioners Court).

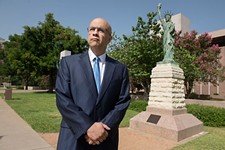

Denton points to his long record of reform in establishing and then presiding over County Court at Law No. 4, the overburdened domestic violence court. He advocated for such a court while serving as head of the C.A. criminal division and was elected to and presided over it since 1998. As Denton recounts it, his court was crucial to reversing public and official neglect of intimate partner violence, taking family violence seriously, and first prosecuting and then presiding over cases that earlier would have been overlooked or dismissed as unserious.

"Over the years," Denton says, "that court and those reforms have led to lower domestic homicide rates in Travis County – as I understand it, the lowest rate of major cities in Texas." Denton argues that the alleged CCL4 "backlog" – sharply criticized by the criminal defense bar – is in fact a "caseload" problem, and he has persistently asked county commissioners (thus far in vain) to create a second domestic violence court.

On the civil side, Denton and Eiserloh have each argued that the C.A.'s Office should take a more aggressive stand against corporate polluters (and on environmental questions generally), and Denton adds that he would sue state government (and specifically Gov. Greg Abbott) for unfair state mandates on local jurisdictions. Garza has made similar statements, emphasizing "pushback against state overreach" on such discriminatory policies as voter suppression.

With so much agreement on policy, the candidates distinguish themselves on specialized experience and "insider/outsider" distinctions. Denton and Eiserloh are longtime Travis County courthouse habitues and veterans of the C.A.'s Office, which they certainly consider strengths. Their campaigns have raised eyebrows over what they consider Garza's limited legal experience (she has been largely "inactive" as an attorney while serving on Council) and her lack of direct experience with the C.A.'s Office. Garza cites her courtroom experience in the attorney general's Child Protection Division – and says it might well take an "outsider" to make managerial decisions long-timers wouldn't try. As a defense attorney, Selvera argues he can bring a fresh perspective from the other side of the courtroom – and less deference to the officeholder courthouse culture.

Too Much Reform Already? County Court at Law No. 4

Curiously, Denton's promotion of his record (as prosecutor and judge) in family violence matters is a more contentious issue in the CCL4 judge race than in his own. The race pits incumbent Judge Dimple Malhotra against two criminal defense attorneys, Margaret Chen Kercher and Tanisa Jeffers (also an Austin Municipal Court associate judge). All three were candidates for interim appointment by the Commissioners Court, and after some awkward political jockeying among the commissioners, Malhotra – then head of the D.A.'s new Family Violence Unit, and formerly chief prosecutor in this very court – eventually got the nod ("Travis County Prosecutor to Fill County Court at Law Judicial Seat," Oct. 8, 2019). Now the former finalists are facing off against each other in the primary.

Malhotra says it is precisely her experience as a family violence prosecutor that has prepared her well for this judicial seat. "Everyone impacted by domestic violence," she says, "including the accused, deserves a judge ... who understands the complexity of these cases ... and who can balance passion with the necessary impartiality demanded by fairness." Her opponents say they fear her experience as a "career prosecutor" suggests potential bias against the defense – that argument runs as a subtext in the candidates' public exchanges.

It is also part of a larger argument over Denton's legacy in CCL4. Some members of the defense bar complain that the "culture" of the court has made their jobs unfairly difficult because "the pendulum has swung too far" in favor of accusers over the accused, and that even the default terminology (e.g., domestic violence "victims" or "survivors" rather than "accusers") presumes guilt rather than puts that question before the court. Shortly after Malhotra was appointed, the Austin Criminal Defense Lawyers Association wrote to the new judge, asking her to address the "backlog" (i.e., delay) of cases, to grant more personal bonds, and, more broadly, to undo what they consider the court's atmosphere of partiality toward accusers, including too much influence of victims' advocacy groups.

Malhotra has since addressed the caseload issue, getting agreement from other judges to accept "non-intimate partner cases" of misdemeanor violence (estimated at 10-15% of the total), reducing continuance requests, and scheduling more trials. She told the Chronicle she doesn't agree that the advocacy groups (who assist those requesting protective orders) exert undue influence, and she has reached out to the defense bar for collaboration going forward.

It's too early to tell if Malhotra's changes will mollify the defense bar (or improve the process of justice in CCL4), and it's unlikely that they will have much effect on the foreshortened primary campaigns. But the arguments serve to illustrate that "criminal justice reform" is often (as Margaret Moore has remarked) "in the eye of the beholder." The people demand less punishment, fewer prisoners, better equality of treatment – and also that cops, prosecutors, and judges arrest, convict, and incarcerate "violent criminals" without hesitation or remorse.

We're all criminal justice reformers now – but quite often the arguments for "reform" reflect either curious contradictions or significant omissions. For example, essentially all the candidates in these races have expressed an informal consensus that we overprosecute low-level drug offenses, and that in the wake of the Legislature's hemp legalization, we should no longer test for THC content in cannabis or K2: "The tests are both expensive and unreliable," is the common refrain.

All well and good. Yet in those same campaign discussions, there has been little or no mention of the recent Downtown crisis of K2 overdoses, or of the burden that drug market imposes on neighbors and businesses. Similarly, there has been virtually no discussion of gun violence – either that associated with local drug dealing (marijuana along with the rest) or the more general plague of gun violence that afflicts Central Texas as it does the whole nation. These are serious, communitywide law enforcement, prosecution, and judicial concerns, and thus far we haven't settled on the "reforms" that might substantively address them.

Got something to say? The Chronicle welcomes opinion pieces on any topic from the community. Submit yours now at austinchronicle.com/opinion.