Austin’s Sexual Assault Controversies Roil the District Attorney’s Race

Margaret Moore's controversial handling of rape cases brings opponents to the race

By Sarah Marloff, Fri., Feb. 7, 2020

How does it feel seeing sexual assault become an election issue?

"It's about fucking time," Erin Martinson tells me over coffee. Martinson jumped into electoral politics to run against Travis County District Attorney Margaret Moore, she says, to stand up for rape survivors whose rights she believes are being ignored by the incumbent and her office.

Martinson's fellow challenger José Garza agrees that a root cause for the "current crisis we are in" over Austin and Travis County's handling of sexual assault "is the fact that, in 2017, the district attorney walked away from survivors and turned her back on advocates." In the three years since Moore took office, collaboration between survivors, advocates, and law enforcement has broken down. The D.A. and her office have been accused of mistreating rape survivors; Moore, her First Assistant Mindy Montford, and the office have been named in two federal lawsuits over these events.

As Garza notes, Moore also ended the D.A.'s longtime collaboration with the Austin/Travis County Sexual Assault Resource and Response Team (SARRT), which Martinson has served on for several years. Since 1992, that task force has worked to improve the local response to rape and the treatment of survivors, bringing together advocates, law enforcement, forensic nurses, and legal entities. Across the country, SARRT groups are considered a best practice, and Austin's has been applauded by entities like Human Rights Watch. Many say that the group's critical work is weakened without the D.A.'s Office at the table.

The incumbent sees what's at stake in this race differently. Moore told me in an email interview that she believes voters should look at her across-the-board record as a criminal justice reformer, including "access to justice, fairness, focusing resources on violent crime, compassionate treatment for victims, and transparency."

But events since Moore first ran to be Travis County's top prosecutor have altered, perhaps permanently, how the public views and discusses rape. The 2016 trial of Brock Turner – the Stanford swimmer who sexually assaulted an unconscious student behind a dumpster – brought to light the appalling reality of how rape is (mis)handled by our criminal justice system. Advocates like Amanda Lewis, co-founder of Austin's Survivor Justice Project, say it's shocking Turner spent any time in jail: "In the field, you know people don't get held accountable, but you start to realize the outside world thinks they are."

Then the stories of Harvey Weinstein's crimes broke in October 2017, kicking off the #MeToo movement. A year later, many watched in horror as accused assaulter Brett Kavanaugh ascended to the U.S. Supreme Court. Kelly White, co-CEO of the SAFE Alliance, the local nonprofit that works with sexual assault and domestic violence survivors, credits these two moments with "elevating" the conversation on sexual assault nationally. In Austin, that conversation was well underway amid the fallout from the collapse of the Austin Police Department's DNA forensics lab and its failure to test hundreds of rape kits. Throughout Moore's term, the "crisis" Garza describes has gotten increasingly intense – leading to what many have described as a "perfect storm" of events that now dominates the 2020 primary race.

Lewis, Martinson, and White say that in their decades of advocacy, they've never seen sexual assault gain this much clout in a political race. "I've seen the arc of time and change," said White. "I've seen us come so far in understanding and recognizing child abuse and domestic violence, and the one that's been the hardest is sexual assault. It's about time it came to the forefront where we can shine light into the dark corners."

The Survivors' Lawsuit

In June 2018, three women rape survivors filed a class action civil rights lawsuit in federal district court against Moore, her predecessor Rosemary Lehmberg, the APD, and the city and county themselves. The survivors' lawsuit, which was amended that August with five additional plaintiffs, argues systemic failures within the local criminal justice system have not only harmed these survivors, but led to gender-based inequitable treatment of all women survivors, which violates their Fourth, Fifth, and Fourteenth Amendment rights.

While APD's questionable handling of sexual assault cases has a starring role in the class action, Moore and her office are accused, at length, of discriminating against women survivors and perpetuating a culture of "disbelieving, demeaning, and ignoring" them. It's also alleged that Moore's office fails to prosecute cases when the victim hasn't been severely injured.

The class action, which explicitly details the plaintiffs' reported rapes, suggests there's "overwhelmingly no justice" in the local criminal justice system, where rapists are repeatedly allowed to "walk freely to rape again." As in other civil rights lawsuits, the plaintiffs do not seek damages, but an injunction ordering the defendants to reform their practices. In December 2018, U.S. District Judge Lee Yeakel heard the defendants' motions to dismiss the case, but more than a year later, he has still not ruled on the matter.

At a June 2019 Public Safety Commission meeting, Jennifer Ecklund, an attorney representing the survivors, said an additional 75 to 100 women have reached out regarding the handling of their cases. More women, Ecklund assured, would add their names to an amended complaint (if and when Yeakel rules), concluding, "Sexual assault cases are not being filed and are not being prosecuted. ... Virtually no rapists are going to jail."

Emily's Story

At 24, Emily Borchardt is not going to become "a hateful person," as she puts it. The young woman and her sexual assault case have made headlines across the state and nation over the last year after she filed a defamation suit, also in Yeakel's court, in September 2019, accusing Moore and Montford of lying about her rape. Borchardt told me on a recent Sunday afternoon phone call that she filed it, "simple as it is, because the D.A.'s Office lied about me and I can prove it and it was the right thing to do." (Moore and Montford filed a motion to dismiss in that case in November 2019.)

"I felt more empowered, or, I don't know, like I had more agency right after the assault – like I survived it. You know?" said Borchardt, one of the plaintiffs who joined the class action suit in August 2018. Her experience with the APD detective handling her case, and then with the D.A.'s Office, changed that. "It starts to take away that sense that you are a survivor."

As recounted in both lawsuits, Borchardt says she was kidnapped by her rideshare driver and taken to a local motel where she was brutally and repeatedly raped by several men over the course of two days in January 2018. She was a UT senior at the time. According to a recent civil filing, Borchardt received a sexual assault forensic exam shortly after her reported attack, during which the nurse "confirmed the presence of bruising consistent with strangulation" and said her body "showed signs of forced intercourse." Four days later, according to the filing, Borchardt's gynecologist "also confirmed obvious signs of forced intercourse."

Twice, the D.A.'s Office declined to prosecute Borchardt's case – the first time before she was formally interviewed by Austin police investigators, when the three alleged rapists, one of whom previously served time for murder, claimed the sex was consensual. The second time came after Borchardt sat for two hours with APD and later provided a written statement in which she insisted she never consented, tried to escape, and feared for her life throughout the ordeal. (In her statement, Borchardt wrote: "I tried to run to the door to get out but he grabbed me by the hair and pulled me back. I learned that trying to run away or hitting him made things worse for me.") Borchardt confirmed to me that neither Moore nor Montford – indeed, no one from the D.A.'s Office – ever spoke to her, before or after declining her case.

However, as became public – notoriously so – last March, Montford did< talk to Dawn McCracken, her former sister-in-law and a family friend of the Borchardts in Corpus Christi, who had reached out three weeks earlier to find out why the case had been declined. Throughout that 38-minute phone call, which McCracken recorded, Montford shared private – and seemingly false – information about Borchardt's case according to the transcript included in Borchardt's defamation suit.

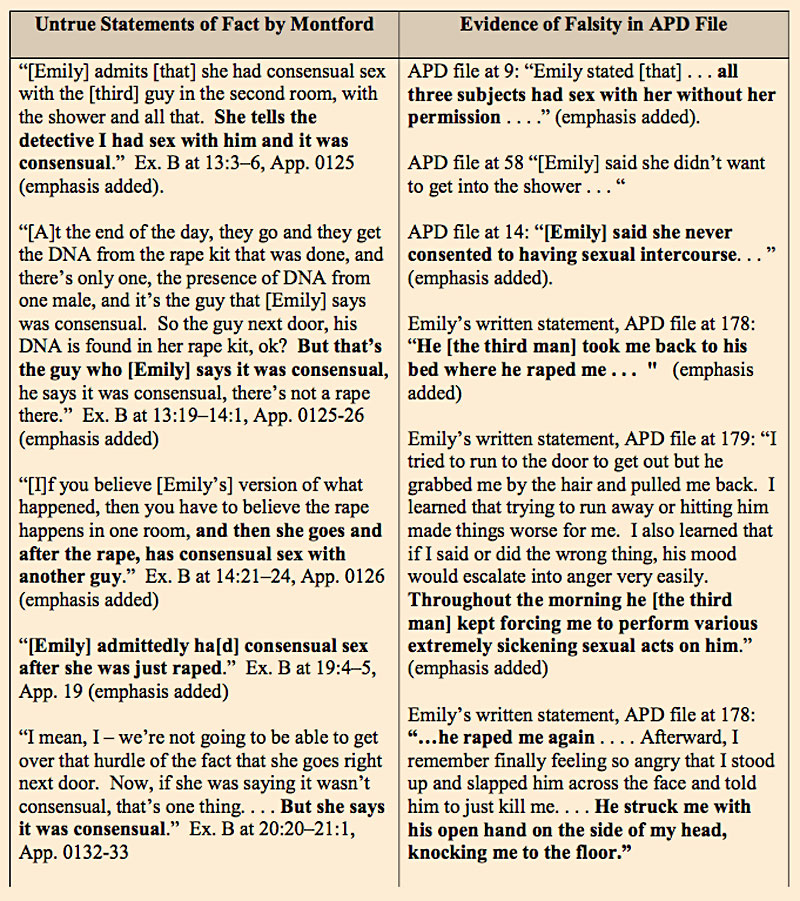

Specifically, Montford said that Borchardt told APD and indicated in a written statement that the rapes were consensual; the APD file contains no such document, nor does it say Borchardt consented to sex during any point in her kidnapping. Montford not only had access to the police file, but told McCracken she studied it "just before" calling. A chart included in a later filing in the lawsuit compares, side-by-side, Montford's statements to McCracken and Borchardt's statements within APD's case file, showing a large discrepancy between the two.

"In the beginning you're in a state of shock or numbness," Borchardt told me during our conversation, referring to the call. "You believe society operates according to certain principles, and then when that belief system is shattered, it's ... I don't know, there's just this void or confusion or this sense of absurdity in regards to the whole thing."

Now, as the election nears and she and the other plaintiffs await Yeakel's rulings in both cases, Borchardt says she "really dislike[s] the uncertainty I deal with every day – being held within a state of suspension, not being able to fully move forward and embrace life." She says the waiting game has meant she hasn't really been able to heal from the assault, adding: "I feel like I spend more time dodging psychological land mines." With the filing of the defamation suit, Borchardt said it "feels like I'm stepping outside the other plaintiffs ... to be scrutinized more by the public."

Yet her decision to go public, using her real name in the suits instead of a pseudonym, "came out of the fact that I think it's kind of a shame that still today, in our progressive Western society, people still have to ascribe the word 'brave' to survivors who've lived through this and come forward, when in reality that stigma shouldn't exist and it should be treated the same way any other crime would be."

When Montford's statements first came to light, Moore defended her chief deputy's actions, insisting in a media statement that "allegations of impropriety are unfounded." Moore said Montford "believed she was providing information" to Borchardt through an "intermediary acting on [her] behalf." During our email interview, Moore confirmed Montford remains on her staff – and will maintain her title as first assistant if Moore is reelected. When asked if Montford had been held accountable for sharing private case information with a third party, Moore said she stands by her previous comments, adding: "As you know, I disagree with your assumptions and your characterizations."

About Prosecuting Rape

All sides of the issue, and in the current election cycles, agree that prosecuting sexual assault cases is inherently difficult. Martinson has called them "historically messy cases that prosecutors don't love handling." Lewis argues that the system itself is not set up to protect survivors; Moore and White note juries are still wishy-washy on rape cases, and Moore also reports that survivors struggle with staying engaged in the lengthy, often painful process. Others, including former APD Sgt. Liz Donegan – a former SARRT co-chair and current candidate for sheriff – believe nothing will change without bringing more cases forward and educating jurors.

Since taking office, Moore has argued some cases are declined because her prosecutors are tasked with proving – beyond reasonable doubt – that perpetrators acted within the Texas Penal Code's definition of adult sexual assault (Sec. 22.011). This requires penetration without the consent of the victim and suggests that a victim has to either fight back, be coerced, or be incapacitated to establish lack of consent. In March 2019, Moore told me that means more than a victim saying, "Hey, I don't want to do this."

According to the survivors' lawsuit, during a 2018 Circle C Area Democrats meeting, Moore reportedly described "nonconsensual sexual 'incidents' involving acquaintances of female victims" as "traumatic occurrences" rather than sexual assault, and suggested such attacks (which form the majority of sexual assaults) are not criminal. During the same meeting, Moore also allegedly stated that rapes "involving victims who had consumed alcohol or drugs are generally not prosecutable as criminal acts."

Moore's opponent Martinson, in a media statement, acknowledged there are challenges when prosecuting sexual assault cases where the victim has been drugged or is drunk, but wrote that "the Penal Code criminalizes sexual assault when someone has not consented." She continued: "There is a network of trained and experienced expert witnesses in our community who can help educate a jury about memory impairment, both from trauma and from substance abuse."

In Texas, on average, it's believed that less than 10% of survivors report to law enforcement. Annually, according to the survivors' lawsuit, roughly 1,000 sexual assault allegations are made locally; only a handful of those make it to the D.A.'s desk. According to the D.A.'s Office, 13.5% of the cases it took to trial in 2019 were for sexual assault (seven out of 54 trials), up from nine out of 76 trials in 2018 and only one of 79 trials in 2017 (in a case involving a male victim).

Moore says of 2017's appalling numbers that the closure of APD's DNA lab delayed "many" cases. Many sexual assault cases end in guilty pleas, but advocates worry many perpetrators plea to lesser offenses (of the 36 pleas obtained in 2017, 24 were for crimes other than sexual assault; of 48 pleas in 2018, 29 were for other offenses, including 12 misdemeanors).

As in other criminal justice matters, structural racism can also influence how cases move through the system. Moore's opponent Garza says women survivors of color – over 50% of survivors in Travis County, he says – face a higher burden when seeking justice. Yet Amanda Lewis of SJP says that, in the eight years she's been advocating in Austin, she's never seen a conviction involving a Black survivor.

According to Lewis, people tend to report when it's "so bad they need to do something" to prevent others from being victimized. For people of color who choose to report, Lewis said, it's important that those cases move forward; otherwise, it only confirms that the criminal justice system isn't set up to protect them.

On the campaign trail, Garza too has expressed this sentiment, often quoting that while Black Austinites make up only 9% of Travis County's population, 25% of the jail's population is Black. (Different sources have different figures, but none dispute this disparity.) Calling our current system "broken," Garza told me, "What I've seen, felt, and heard in conversations across the county is that the injustice that women are feeling and experiencing ... is the same injustice that people of color are feeling, that working class people are feeling."

Crimes That "Matter"

In a quiet cafe, Lewis explained that in her opinion, Travis County has "flagged" the types of rape that "matter" – i.e., stranger rapists, sober victims, rapes where a weapon is involved. Those, however, don't represent the majority of assaults. What about Borchardt's case, which would seemingly be one that "matters"? "Emily's case just lends itself to more inconsistencies [within the system]," Lewis said.

Another case Lewis cites is that of Marina Conner, also a plaintiff in the survivors' suit, who reported being raped in a Downtown parking garage. Despite physical evidence – and a voice mail Conner left on a friend's phone of her screaming "no" during the attack – her case was declined for prosecution because there was no DNA in her rape kit.

According to Conner, Assistant D.A. Mona Shea told her that Moore's office couldn't prosecute her case without DNA evidence, due to the "CSI effect" – meaning that TV procedurals have misled jurors to believe DNA evidence is required for a conviction. "I feel like the 'CSI effect' is just an excuse for them to get away with trying less cases," Conner told me. "I don't doubt all the crime shows on TV have changed what juries expect, but that doesn't mean you shouldn't work as a prosecutor to overcome whatever perceptions the public have."

In November, Borchardt sought a temporary restraining order against Moore and Montford to stop the pair from making, directing, or encouraging others to make "statements that explicitly or implicitly state or suggest" she consented to her rape. According to her filing, Moore has continued to discuss the case on the campaign trail, referencing an Oct. 13 candidate forum in Lago Vista when the D.A. reportedly said, "In this case, the allegation that there were lies told or that it was a violation of victim privacy are unsubstantiated."

Calling victims liars "feeds into incredibly dangerous, painful, and disproven myths that women lie about rape," attorney Elizabeth Myers, who along with Ecklund is representing Borchardt and the other plaintiffs, told me. "It's one of the reasons women won't come forward. And this feeds into one of the most insidious false narratives about rape. To have a D.A. publicly aligning herself with a perpetrator, supposedly wrongfully accused by all these women – it's tone-deaf and also incredibly damaging."

The lawsuits have amplified the conversation both locally and nationally, with The New York Times, ProPublica, and Newsy all having covered Austin's handling of rape cases. But many advocates say the system began splintering before a single suit was filed, with the breakdown of collaboration at the Austin/Travis County SARRT.

The Broken SARRT

In mid-2017, Moore left the SARRT after its then-co-chairs sent a heated letter to city and county officials calling the APD rape kit backlog a symptom of a "diseased system that condones rape and does not hold perpetrators, or itself, accountable." The letter was sent shortly after a mold-like substance was found on 849 untested rape kits; at the time, Moore told reporters, "The most important thing is [the mold] didn't affect the disposition of these cases. ... There's a backlog, but that backlog is caused because these aren't high enough priority to be fed into the capacity we currently have. It's only for informational purposes; it's not for prosecution." The letter insists "each kit represents a survivor's hope for justice and need for safety."

Moore has described the letter as "ugly," and while those and subsequent SARRT leaders have asked the D.A.'s Office to return to the group, Moore has continued to decline invitations. I asked Moore in January if she would consider rebuilding connections with the SARRT and with advocate groups; Moore simply responded, "Of course. I am in favor of collaboration." Days later, Moore elaborated that she plans to continue working with "collaborative partners like SAFE."

The SAFE Alliance is part of Moore's Interagency Sexual Assault Team (ISAT), formed in September 2017 with local police and sheriffs' departments. Like the SARRT, the ISAT seeks to increase the county's effectiveness regarding "response, investigation, and prosecution of adult sexual assaults and to ensure that victim needs are being met."

"We're doing that [work] with ISAT now," Moore told me via email. "The important thing is the WORK not the organization that does it."

During the Chronicle Editorial Board's recent endorsement interview with the D.A. candidates, Moore said the lawsuits need to be resolved before she'd consider working with SARRT, claiming the task force was "instrumental" in the creation of the lawsuits against her and responsible for soliciting additional plaintiffs. At the Jan. 11 Northeast Travis County Dems and Black Austin Democrats endorsement forum, when Garza accused Moore of walking away from the task force, she responded: "This talk about walking away from SARRT, I don't know what you would do if a group sued you, but that was what happened. We did not stop going to SARRT until they actively recruited plaintiffs in their meetings and my people felt very uncomfortable."

Martinson, during the Chronicle meeting, vehemently disagreed with Moore, insisting SARRT had no part in the lawsuits or soliciting survivors. Her fellow SARRT members also dispute the D.A.'s version of events, noting Moore exited the group a year before the lawsuit was filed. In the meeting, Moore also said the issues of strained collaboration between advocates and law enforcement began before she arrived – leading advocates to wonder why the self-proclaimed reformer D.A. would turn away rather than try to fix what was broken.

"A Long-Held Rage"

Though Martinson said frustration over Moore exiting SARRT helped propel sexual assault issues into the current D.A.'s race, she believes the D.A.'s tensions with advocates date back even earlier, to when Moore cleaned house before taking office in late 2016. As the Statesman reported at the time, 17 attorneys, 12 investigators, and six administrative staff retired or were removed under Moore.

While it's common to see turnover when newly elected officials take office, some of the prosecutors Moore chose not to retain were ones whom advocates considered experts in sexual assault cases, including former SARRT co-chair Dana Nelson, who worked to secure the grant that helped fund Moore's Adult Sexual Assault Unit. Moore told me only 12 veterans of Lehmberg's office who applied to work under her were let go – and only four of them had prosecuted a sexual assault trial between 2010 and 2016. (According to her numbers, only five sexual assault cases went to trial in those years.)

When deciding who to retain, Moore said she took into account "trial strength, adherence to ethical standards, work ethic, and team spirit" to build a "team that would provide superlative service to the State and this Office," noting the D.A.'s Office is "now prosecuting more cases than when those people worked here."

SAFE's Kelly White agrees the county has "come a long way" since then, but over the course of the last fiscal year, ending in October, SAFE's forensic nurses handled 661 sexual assault exams. "That's a lot," noted White (although not all of those survivors sought to report to law enforcement, which SAFE does not require). While White declined to discuss Moore, the lawsuit, or the firings specifically, she noted that the low number of prosecutions before Moore took office – when combined with APD's rape kit backlog and the national conversations around sexual assault – spurred advocates and survivors to call "bullshit."

"It came out of a long-held rage," said White. "People have for way, way too long been angry – all people, but let's be honest, sexual assault is largely a crime against women by men. Often women are discounted and blamed, called liars. It was building, and the culmination is coming out in [the district attorney] race." (To a lesser extent, it's also playing out in the sheriff's race, where incumbent Sally Hernandez also eventually left the SARRT and now faces Donegan in the primary.)

Over the course of reporting this story, several people declined to speak with me both on and off the record for fear of retaliation by Moore and the D.A.'s Office. "It's real," Lewis told me candidly. "This is the most powerful law enforcement official in the county, and yeah, I think that retaliation has been pretty widespread." Lewis believes that in Travis County and even statewide, "law enforcement sees any criticism as a threat to their power and their credibility instead of an opportunity to do better." Moore responds: "These charges are baseless. Neither I nor my office engage in retaliation toward critics. I suspect there is a political agenda motivating these false charges so close to an election."

"False Political Rhetoric"

Moore tells me she's worked since "Day One" to address the unmet needs of survivors – creating the Adult Sexual Assault Unit, with two prosecutors trained to support victims and witnesses, along with a grant-funded position for a Victim Navigator to help survivors stay engaged in the process. (The general unresponsiveness of the D.A.'s Office is one of the complaints put forth in the survivors' lawsuit.)

While campaigning, Moore has accused advocates and survivors of bullying her and the office; she told me a better way to put it would be that "unfair and inaccurate" statements have been made about the people in her office. According to Moore, the "truth is that this office has greatly increased" resources and focus on sexual assault investigations and prosecutions. "I am always offended when voters are misled by false political rhetoric. But most of all – I hate what this false narrative does to discourage victims to report."

Over the last year, Moore has worried to the media that the lawsuits and ongoing coverage of the controversies would have a negative effect on victims coming forward, and in 2019, SAFE reported a decline in survivors seeking services – the first in four years. But Lewis argues that a decline in reporting "is an indictment of our system." She admits that "being honest" about the system's realities could likely make fewer people feel confident in reporting, but said local advocates "believe in radical transparency and informed consent. People should know what's going to happen – what they're getting into. It's that knowledge that will hopefully push our systems to change."

If change doesn't happen, Lewis says the fault falls on the people in power – who in Travis County are instead issuing blame: "They're saying, 'It's not that we're not doing a job, it's that you're talking about it.'" But staying silent, says Lewis, only maintains the status quo. "If you don't talk about systemic issues, they're going to keep happening and maybe get worse – versus talking about it, and maybe it gets better."

Borchardt echoed Lewis' sentiments, telling me she feels Moore "criticizing women who do come forward, who use their names, is dissuading other victims from coming forward. It's like she's saying that women who choose to speak out and hold the system accountable are out of line, when [in reality] speaking out is what's caused some changes to be made, at least temporarily."

Still, Moore insists she's committed to supporting survivors, noting that rape is a "terrible crime" and a "very emotional issue." Over the years, "deep dissatisfaction and anger over the law, criminal justice system, and the unmet needs of victims have built up," and now she says her office is working to reverse the "ingrained culture and legal issues that make these cases difficult to prosecute."

Moore says there's "no question" there are some cases "where the [rape] accusation is true, but we simply don't have enough evidence to pursue the case," which she described as "one of the most horrible and painful experiences a prosecutor deals with." Yet Lewis and Martinson say basic victim rights are not being addressed. Aside from prosecution rates, Lewis said, "There are processes in place to [ensure] survivors' rights are being respected."

Those rights, which include access to case information and regular contact with prosecutors, are as important to advocates as convictions. According to an August statement from Martinson, over the past few years, she's heard from "dozens of victims" who say the same thing about working with the D.A.'s Office: They "did not feel believed, their cases were minimized, and [they] felt re-traumatized by having reported their cases."

In regard to victim contact and prosecution, Moore said, "I very much understand the desire to have your day in court, and the rage and pain and desire to see perpetrators brought to justice. Emotionally, I want that to happen for every single victim. But I am charged by the state of Texas with the job of only pursuing cases where evidence meets a certain threshold." Moore emphasized that this legal restriction is on the books to "protect the falsely accused." Referencing the Central Park Five – the Black Harlem teenagers wrongfully convicted of raping a white woman in 1990 – Moore noted that Black men are "disproportionately victimized with false accusations." (Though finding an exact number is difficult, experts say false accusations are rare; neither RAINN, SAFE, nor UT's Institute on Domestic Violence & Sexual Assault share this statistic.)

What Happens Next

In the wake of #MeToo, as early voting nears, Travis County residents will be asked to consider where they, too, lie on the conversation around sexual assault. "Everyone's asking, 'This is so widespread, what are we doing about it?'" Lewis says. That question has spurred a local movement where voters, advocates, and survivors are seeking accountability from the people in power.

If elected, Martinson and Garza both promise to return to the SARRT in an effort to resume greater collaboration. Both say they're eager to work closely with advocates and survivors to improve the system. Moore promises to continue building on ISAT and her Sexual Assault Unit. But moving forward will take work, regardless of who wins. As Lewis summed up, whoever sits in that office has to want to progress through a "process of being honest and owning" their part. Ultimately, it's trust that has to be rebuilt, because without trust, Lewis said, "You don't get to the bigger issues that require honesty and transparency."

Got something to say? The Chronicle welcomes opinion pieces on any topic from the community. Submit yours now at austinchronicle.com/opinion.