Hiring More Police Is Not a Great Way to Prevent Murders

A closer look at Austin's growing number of homicides

By Austin Sanders, Fri., Oct. 15, 2021

Each of the following statements is true:

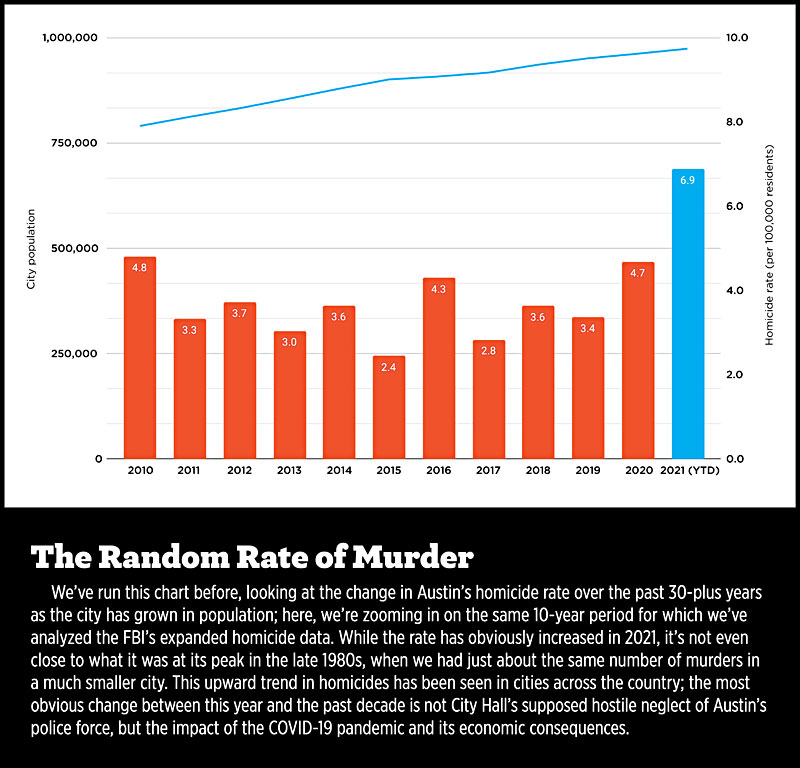

• Austin police have reported more homicides in the past 10 months than in any year on record.

• The murder rate through 2020 and the first nine months of 2021 is less than half of its previous high, set in 1984.

• Cities large and small, progressive and conservative, ones that cut their police budgets and ones that increased them, all over the U.S., have seen many more homicides this year and last than in any year in the prior decade.

• This increase in murders began before anything that could be characterized as a "defund the police" movement, in Austin or anywhere else (in March 2020, homicides in Austin had increased 100% year-over-year).

• As of last year, Austin remained one of America's safest big cities. In 2020, of the nation's 30 largest cities, Austin ranked No. 27 in violent crimes per 100,000 residents, according to the FBI's Uniform Crime Reporting database.

The emotional reaction to the first of these facts has overshadowed the reality of the rest. This November, voters are being asked to approve a major new investment in police staffing – one that proponents say is obviously needed, given the rising number of murders. This boost in the size of Austin's police force, indexed to the city's population and guaranteeing that officers can spend up to one-third of their duty hours as "uncommitted time," will be expensive, and nearly irreversible under Texas law, and can't be paid for without future voter-approved tax increases or drastic cuts in current programs and services. Those are also facts.

It would make sense for the city to invest in programs that actually prevent violence, rather than in efforts that have little or no effect in reducing homicides. That conversation was already underway last year when the killings of Houston native George Floyd in Minneapolis and Michael Ramos here in Austin led to massive protests against police violence that were met by more police violence. The subsequent commitment made by City Hall to "reimagine public safety" has been built around funding crime-prevention alternatives to policing that are less expensive and more effective. It's in reaction to that "reimagining" movement that supporters of the policing status quo mobilized to get Proposition A on the November ballot; the increase in murders (which, again, is happening everywhere) has given them a hook on which to hang their campaign.

Is increasing police staffing, indexing it to Austin's population, and giving officers more uncommitted time to build bonds with communities an effective response to our rising murder rate? To know the answer, we need to know what causes are leading to Austin's growing number of homicides. By understanding what Austin murders look like, we can better identify and fund solutions that will prevent them, even if those solutions are politically difficult and challenging to implement.

What the Data Shows Us

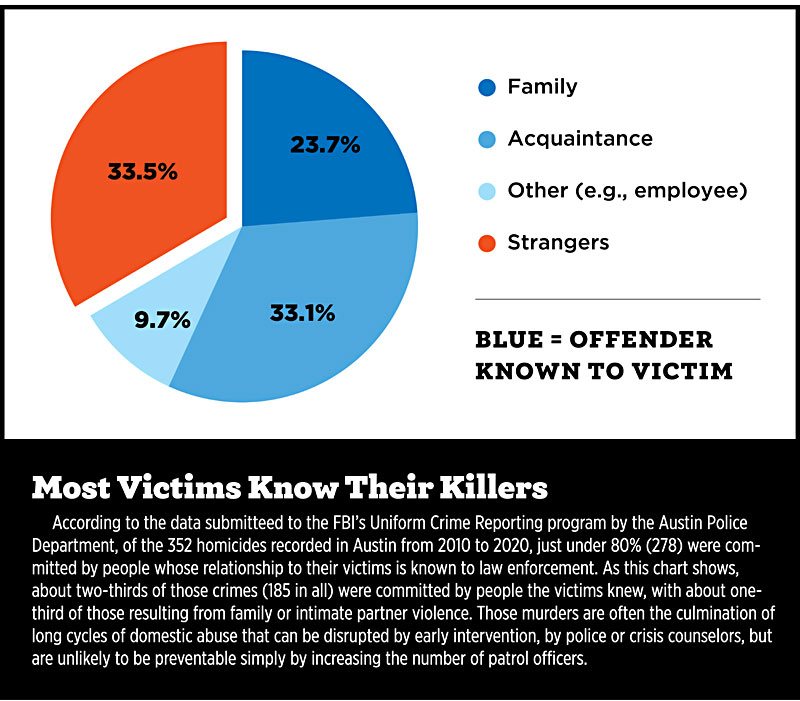

To do that, the Chronicle analyzed 10 years worth of Austin homicide data (2010-2020) from the FBI and the Austin Police Department. Our sources include the FBI's "expanded homicide data," which has been published annually as a supplement to the bureau's Crime in the United States report of UCR data, which while imperfect is the most comprehensive source of information on crimes reported to law enforcement. (This year, the FBI is moving to a digital-first presentation of this data through its Crime Data Explorer portal.) The expanded homicide data includes contextual information such as the relationship between victim and offender; how victims are killed; what circumstances led to the murder (e.g. an argument or a robbery gone bad); as well as demographic data on both victims and offenders. We used data pulled from the city's Crime Reports page to determine in what types of locations (homes, motels, parks, etc.) murders occurred most frequently.

Here's what we found: Over the last decade, most murders in Austin occurred between people who know each other, as a result of some kind of argument, with a firearm (usually a handgun), and in places where police officers normally would not patrol. The first three characteristics are commonly observable and are captured in the FBI's expanded homicide data. The last is more subjective; we've sought the advice of experts as we've identified the types of locations where officers are unlikely to patrol. A plurality of homicides have occurred inside private residences or hotel rooms, where police are generally not allowed to enter on patrol.

About 18% of homicides during the decade were committed by the victims' spouses, intimate partners, parents, children, or friends. Advocates for survivors of domestic violence say that such homicides can follow a buildup of tension over time, with escalating acts of control perpetrated by an abuser. "A lot of times in these cycles, the violence gets more severe," Coni Huntsman Stogner, vice president of community services at SAFE Alliance, told us. "The violence escalates as a means of control. Maybe the [abuser] starts with controlling access to car keys. Then that method of control doesn't work, so the abuser shoves their victim against the wall. When that level of violence loses its intended effect, then a more violent assault can occur. Sometimes, the violence escalates to murder."

Not Much Rational Thought

In those cases, a homicide may be predictable and thus preventable, if the right people – who may not be police officers – can intervene at the right time. In property crimes with an economic motive, such as theft, offenders' behavior can also be predicted and may simply reprise their prior crimes. But rarely is murder anything but an irrational and spontaneous act, committed in private, with a firearm that kills victims almost immediately. This underscores how unlikely it is for a patrol officer to even encounter an imminent homicide, let alone prevent it.

Phillip Lyons, dean of the College of Criminal Justice at Sam Houston State University – perhaps the state's best-established academic program in criminology – told us in an interview Oct. 5 that, "I'm pessimistic on the idea that homicides can be prevented." Lyons, also a former police officer and consultant to law enforcement, says, "Most of our criminal justice system is premised on the idea of rational decision making, [that] perpetrators [are] constantly weighing costs and benefits of decisions." For example, say you're running behind schedule for a meeting across town. Unless you drive above the speed limit, you won't make it on time, so you take a calculated risk – you break the law by speeding to avoid the consequences of arriving late.

However, "Most of the time when homicides occur," Lyons said, "there isn't a lot of rational thought taking place." Maybe alcohol is involved. Maybe the perpetrators are young, with brains that aren't fully hard-wired for decision-making. Maybe they live with mental health challenges. Or maybe they are just consumed by rage and, in the moment, fail to ask themselves whether the consequences would be worth breaking the law, as they would before deciding to go over the speed limit.

"I'm not hopeful that we can do much to prevent homicides," Lyons concluded. In any event, that's not what Austin police officers and their colleagues spend most of their time trying to do. Law enforcement adds value to the communities it serves by helping prevent other types of crime, and by helping resolve homicides and other violent crimes by apprehending suspects, collecting evidence, and aiding successful prosecution. But crimes that are difficult to predict and that rarely happen in the presence of police are unlikely to be prevented simply by adding more police.

“A Path That Won’t Work”

How the size of a police force impacts crime rates has, unsurprisingly, been studied by criminologists for decades. That research shows increased police patrol can reduce some crimes committed in public spaces where perpetrators are more likely to weigh the consequences of getting caught. Take auto theft as an example; not only the crime of stealing a vehicle, but continuing to use that vehicle on public roadways, gives officers a greater chance of stopping and apprehending suspects. Since the thieves are interested in the economic benefits of their crime, and of being able to commit more crimes, they are more likely to calculate the risks they face than are people engaged in homicidal violence.

Former UT-Austin professor Bill Spelman, now retired from the LBJ School of Public Affairs, has studied crime trends since the 1980s. Initially, his research focused on the effect prison sizes and incarceration rates have on crime, but with that question firmly settled (putting more people in prison does not reduce crime), he's turned his attention to the effect police force size has on crime. Spelman also served three terms, in three different decades, as a member of the at-large Austin City Council, including when the city adopted its first "meet and confer" contract with the Austin Police Association in 1999, which led to two decades of uninterrupted growth in the size of the city's police budget until the "reimagining" efforts of 2020.

That makes Spelman's throwing his weight behind the opposition to Proposition A unusually significant. He sees the initiative, backed by the police union and the GOP-affiliated Save Austin Now political action committee, as an expensive response that would not address Austinites' concerns about the increase in homicides. If it passes, he says, it could engender a false sense of security that "would lead to more people dying" as more effective responses go unfunded. "I felt I could make a contribution [to the campaign] that is different from anyone else," he explained. "I know APD and the assumptions that were necessary to make cost estimates. As a council member, I had to balance competing priorities, which this proposition will not let the Council do. Prop A sets us down a path that won't work. If we want to solve the homicide problem, we need to do something different."

Why is Spelman so confident that Prop A won't work? Because he published a peer-reviewed research paper, "The Murder Mystery: Police Effectiveness and Homicide," in 2016 on the exact question of whether and how larger police forces could reduce murder rates. He analyzed the data and findings of multiple other studies published between 1970 and 2013 and found they failed to properly account for two important factors. One is that murder is still a very uncommon crime; because the numbers are so low, a city's murder rate may appear to fluctuate widely for what are ultimately random reasons.

The other is that police staffing levels are a lagging influence on the murder rate; homicides increase in Year 1, policymakers respond by hiring more cops in Year 2 who are trained in Year 3, just in time for the murder rate to decrease. That decline may have nothing to do with a larger police force; it may reflect a statistical reversion to the mean. But it's certainly the case that police departments, elected officials, and police unions will credit the new officers for the decreasing murder rate.

Spelman uses complicated statistical analysis that we cannot possibly do justice to here, but essentially, he concludes in his paper that increased police force size either has a small effect or no effect on changes in the murder rate. To definitively determine that effect would take years of controlling for other variables; some are within the power of police departments to influence (such as targeted crime reduction strategies), others lie well beyond it (unemployment rates, wage levels, the quality of schools). But to achieve statistically significant decreases in the murder rate just through adding more officers, police force size would need to grow by about 70%.

"So long as the primary justification for more cops is to reduce crime," Spelman wrote in his paper's conclusion, "we need to be more careful with our rhetoric." He notes that more cops can reduce some crime, but when it comes to murder, "effect sizes appear to be modest, at best, and the alternatives are far better ... It's time to stop telling policymakers 'More policing = less crime.' Research suggests a better slogan might be, 'Better not bigger.'"

Joseph Chacon, APD's newly minted chief, agrees that police primarily react to crime rather than prevent it, and that officers are unlikely to stop most violent crimes – especially those that occur between families in private spaces. However, he believes law enforcement can play a role preventing violence that stems from other criminal activity. Chacon says APD's current staffing levels have required moving officers out of specialized units, such as the Metro Tactical unit that assists with narcotics investigations, to keep patrols fully staffed, meaning officers are less likely to prevent violence arising from the drug trade or organized crime. (According to the FBI data, about 3% of the homicides in Austin from 2010-20 were related to drug law violations and less than 1% of murders were classified as "gangland killings.")

"When I talk to my crime analysts we can't point to one issue that's more prevalent than others," Chacon said of what events are leading to the increase in Austin murders. "But some of the homicides we have seen are related to bigger crime issues, such as conflicts between people in different rival groups ... those are areas we can effect, but others like domestic violence calls, we are more reactionary. But I have to have the number of people I need to put these strategies into effect, whether that's through patrol or targeted violence intervention programs."

Interrupting the Behavior

Alternatives that could be more effective than simply hiring more police may emerge from the city's newly established Office of Violence Prevention. For example, most homicides in Austin from 2010-20 were committed with firearms. What would be the impact of a widespread public education campaign on safe gun storage? "Oftentimes when decisions are made to use a firearm, it's a knee-jerk decision," OVP Director Michelle Myles told us. "If a person has to go through trying to unlock the gun or cut it free out of the locking mechanism, it kind of interrupts the behavior" long enough for people to rethink their actions.

Myles is working with APD, local judges, and the Travis County District Attorney's Office to develop a standardized protocol for people to surrender firearms when a court order prohibits them from owning one. Currently, no such procedure exists in Austin; in September, the OVP applied for a federal grant to implement this strategy.

While the gun enthusiasts who have the ear of the Texas Legislature object to efforts to expand "red flag" laws to cover more situations that precede violence, there are plenty of existing prohibitions on weapons possession by past felons, juveniles, persons living with mental illness, those subject to protective orders, and so on. Also in September, Chacon reported a 28% year-over-year increase in weapons violations. In his view, the prevalence of guns on the street that shouldn't be there, in the hands of people who shouldn't have them, has contributed significantly to the recent increase in murders. This includes guns that are stolen from unlocked vehicles or during home burglaries and are later used to commit violent crimes. "We need to make sure that people know how to store their guns safely and securely so they don't end up on the street and in the hands of people who want to commit violence," Chacon told us.

A program often cited by criminologists that involved, among other strategies, reducing the number of illegal firearms on the street is Operation Ceasefire in Boston. A 2001 study found that the gang interdiction program, which included outreach to gang members by respected community members and threats of severe prosecution against repeat offenders, resulted in a 63% reduction in youth homicides.

In High Point, N.C., another effective program focused on early intervention when signs of violence emerged in relationships. This was aided by additional training for officers who responded to domestic violence calls and by more comprehensive reporting that identified perpetrators with a history of abuse. (A 2018 Washington Post analysis of five cities found that "more than one-third of all men who killed a current or former intimate partner were publicly known to be a potential threat to their loved one ahead of the attack.") Five years after High Point implemented its program, murders attributed to violent relationships dropped by 72%.

SAFE's Huntsman Stogner said better officer training and a program aimed at early intervention could prove effective in Austin as well. "I don't think more officers are the answer," Huntsman Stogner said. "But having an increased partnership with [APD] Victim Services, so that trained counselors can engage victims in ways that officers can't is important." Training officers to recognize common responses to partner violence and assault, such as laughing or lashing out at the officer, and taking steps to separate perpetrators and victims before conducting interviews could go a long way in identifying abusive relationships before they become deadly. "The best interventions happen early and take time," Huntsman Stogner said.

A model known as Cure Violence has shown promising results in some cities; it involves deploying community members, known as "violence interpreters," who are able to engage with residents in neighborhoods experiencing violence and begin to mediate conflicts. According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, two years after the Cure model was implemented in 2013, North Philadelphia neighborhoods saw a 30% reduction in homicides, even as the murder rate for the city as a whole increased.

Austin's OVP was only established in 2020, following the recommendation of the Gun Violence Task Force spearheaded by Council Member Alison Alter. Myles, who previously worked in the city's Homeless Strategy Office, was hired in June and contracted with Dr. Chico Tillmon, a research fellow at the University of Chicago's Crime and Education Labs and a national expert in violence prevention programs, to identify gaps in Austin's systems and to recommend partners with whom the city could develop programs that implement best practices from other cities.

So far, Tillmon has completed two reports for OVP; one identifies communities with the highest levels of violence, the other maps out existing intervention programs. A third report will focus on causes of violence, and OVP expects to implement targeted prevention programs beginning later in fiscal 2022, which began at the city Oct. 1.

Austin does have some small, largely grassroots existing efforts. Robert Muhammad established Perfect Manner in 2019 in Killeen, after more than 20 years of varied anti-violence work, and now offers its services in the Austin metro area. Muhammad and his staff of five are conflict mediators; typically they're contacted by, or on behalf of, people caught up in conflicts that are escalating toward violence they wish to avoid. One of their mediators will reach out to the people involved, learn more about what is causing tensions, and if all sides agree, arrange a meeting (face to face, or virtually during the pandemic) to try to hash out differences. "We've found that most conflicts are a result of miscommunication, or puffing up one's ego on social media," Muhammad told us. "Since the pandemic forced people inside where they spent more time on social media, we saw violence spill out into the community once things began opening up. Giving people a space to talk out issues has helped."

Data provided by Muhammad shows that about 53% of Perfect Manner's mediations occurred before any violence took place; another third took place after, but before anyone was seriously harmed. "We are designed to stop the bleeding," Muhammad said. "We have the desire to help out community, but are limited financially. I don't think investing in more police is the answer, because police enforce the law, they don't prevent violence. We need police, but what we need more is investment in social programs that can uplift community members."

Got something to say? The Chronicle welcomes opinion pieces on any topic from the community. Submit yours now at austinchronicle.com/opinion.