A Month After Mike Ramos Died, Some Hesitant Steps Toward Accountability

Justice comes slowly

By Austin Sanders, Fri., June 5, 2020

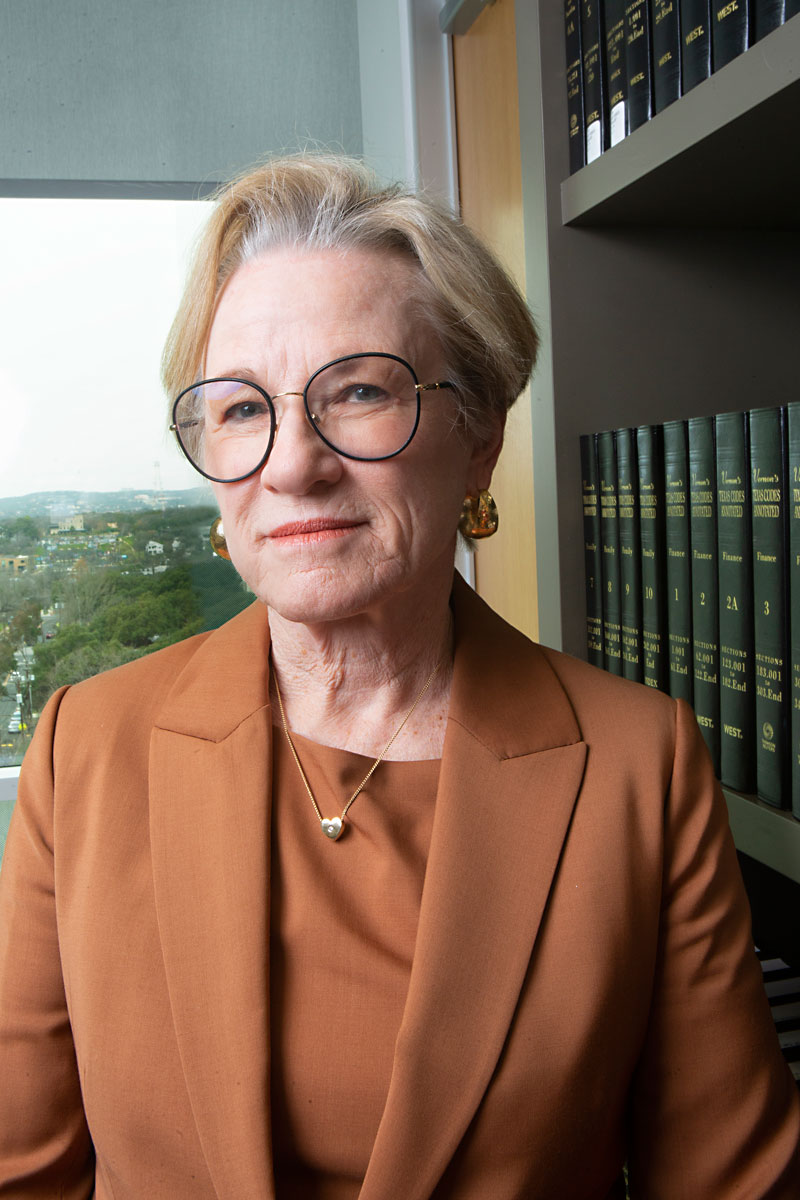

Before Austinites hit the streets to protest police brutality, the wave of unrest rolling across the nation already had one important local effect: It compelled Travis County District Attorney Margaret Moore to decide she would present the fatal police shooting of Michael Ramos to a special grand jury.

In a brief statement issued late on Friday night, May 29 – as the first protests began in front of Austin police headquarters, ahead of previously scheduled weekend events to address the police killings of Ramos locally and George Floyd in Minneapolis – Moore said, "I reviewed the case today with my civil rights director [Dexter Gilford], and we believe the investigation has progressed to the point that we can properly make this announcement."

On the evening of April 24, Austin Police Officer Mitchell Pieper, just three months out of the police academy, shot Ramos with a "less than lethal" beanbag round while his hands were in the air. After being hit, Ramos dove into his car and began slowly driving away from the officers. Still, Officer Christopher Taylor, a 10-year veteran, shot and killed him with a rifle. Ramos did not have a gun on him or in his vehicle.

Once APD detectives confirmed that Ramos had been unarmed, Moore told the Chronicle, the decision to prosecute the case was obvious. The unusual move – publicly announcing that a grand jury would be impaneled, before actually doing so – was an attempt by the D.A. to address the frustration over police brutality erupting around the nation and preparing to hit Austin.

"I normally would not announce the grand jury ahead of time," Moore said, "but in this case, because of the national unrest over Mr. Floyd's death and the local reaction to that wrapping in Mr. Ramos' death, I thought it was important for the people of Travis County to know we are indeed prosecuting the case. I was hopeful that it would help this community."

But as is often the case in police killings, the official actions taken by the criminal justice system leave many unsatisfied. Moore did not say what kind of charges the grand jury would consider, and it's unclear at this time when the presentation would even begin. As with everything else, COVID-19 presents a complicating factor.

The D.A. will need to interview about 50 to 60 prospective members before impaneling a new special grand jury – when convened specifically to address police misconduct, the 12 jurors also undergo training in use-of-force law – but that process will likely happen virtually. From there, prosecutors will have to locate a physical space for jurors to deliberate the case in person. "We've impaneled three grand juries in these cases since Moore has been in office," Gilford told us, "and they are all highly emotionally charged deliberations. So many intangible aspects of communication will be lost if we tried to do this virtually."

Selecting the jurors will be difficult. Ideally, those are people who can be sensitive both to the victim killed by police and to the officer who did the killing. But as protests over extrajudicial killings continue to roil the nation, there are fewer people in that middle. "We might be going through a cultural paradigm shift," Gilford theorized, "but it's also hard for me to imagine that anyone who wasn't already awakened to the reality of police violence is now because of Mr. Floyd's death. I think people on both sides are going to be further entrenched in their own beliefs."

Understaffed & Overworked

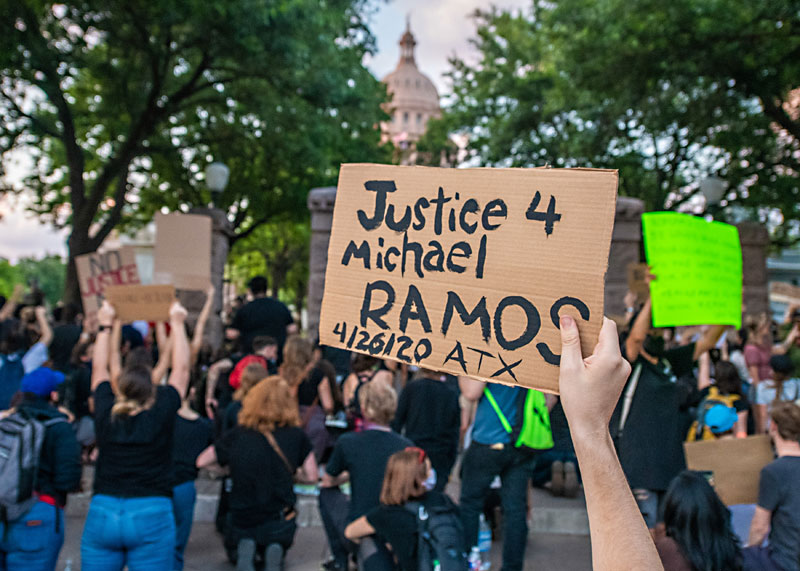

For those who have been advocating for swift action in response to Ramos' death – including the 42-year-old man's mother, Brenda – the D.A.'s actions appear to only be the next phase in a routine cycle, played out again and again, that inevitability ends without justice. Brenda Ramos, who spoke publicly for the first time Sunday, May 31, lamented the fact that she was made a member of the "terrible, heartbreaking club" of "mothers of Black Americans who have been murdered by police."

The D.A. Office's recent track record in grand jury presentations doesn't inspire confidence either. According to numbers provided by Travis County, prosecutors have not secured a single indictment over a lethal use-of-force case since 2015. In that year, seven cases were presented to a grand jury; nine were presented in 2016 and one in 2019, with none resulting in charges against the officers involved.

Ramos also had questions for police Chief Brian Manley about what's become a tragic theme among police killings: Taylor had previously killed another person while on duty, without any apparent consequences. On July 31, 2019, Taylor and another officer, Karl Krycia, shot and killed Dr. Mauris DeSilva, who was undergoing a mental health crisis when he encountered the officers at his Downtown high-rise.

Brenda put the question directly to Manley: "Why was Officer Taylor even on the street and allowed to gun down my unarmed son on April 24?" Taylor underwent no training after killing DeSilva that might have better prepared him for a future encounter that could turn fatal, and as of now, he is still on paid administrative leave – for the second time. Ramos called on Manley to suspend or fire Taylor, but despite her pleas and the case going to the grand jury, Manley has no plans to do so, citing Civil Service law, which prevents him from doing so until internal and criminal investigations of Taylor's conduct are completed.

Why have 10 months gone by since DeSilva's killing without action from the D.A., either to pursue or decline charging the officers? According to Moore and Gilford, it's simply a lack of resources. "I have three lawyers in that unit and they're overworked," Moore told us. "That's just it. The actions and the finishing up [of that process] is taking longer than we expected."

They're understaffed because prosecuting police use-of-force cases has historically not been a priority for most D.A.'s offices, especially in Texas, and even in a city like Austin that bills itself as progressive. And they're overworked because there are simply too many police shooting cases for three lawyers working full-time to process in a timely manner (Gilford's Civil Rights Unit currently has seven cases under review).

For criminal justice activists, it's a perfect crystallization of everything that's wrong with the criminal justice system. "Literally, our criminal justice system can't devote enough resources to the police brutality we have in this town," Chris Harris, a reform advocate with Texas Appleseed*, told us, "and we have a prosecutorial side that is not prioritizing justice. The sheer amount of cases and the inability or unwillingness for the D.A.'s Office to prosecute is just a perfect microcosm of all the frustrations people are protesting over in the first place."

The High Cost of Killing

As criminal justice proceedings drag on, victims of police violence and their families often turn to civil courts for restitution. Because lethal force policies give leeway to officers who feel their life or the life of someone else is threatened – and because officers are trained to use lethal force in only those situations – winning criminal convictions has proved difficult, so settlements are sometimes the only way a victim or their family can earn justice.

No lawsuits have been filed over the DeSilva or Ramos killings, but lawyers representing family members of each victim are considering them. Aspen Dunaway, who is representing DeSilva's father, Denzil, told us in a statement, "We are reviewing the possibility of filing a lawsuit on behalf of our client. Due to the excessive force used by [APD] officers, Denzil lost a beloved son and the world lost a talented scientist and researcher. Although some evidence, such as the officers' body worn camera videos, is still not available to the public due to court order, we look forward to the opportunity to determine why Dr. DeSilva was subject to lethal force when it was clearly not necessary, which led to our client's tragic loss."

Rebecca Webber, who is representing Brenda Ramos, said her client is ready to file a lawsuit against the city if necessary, but hopes that it won't be. "Maybe I'm naive," Webber told us, "but I have some hope that this shooting will be a turning point and that the city will not continue to defend indefensible conduct by police officers. Ms. Ramos should not need to file a lawsuit to prove what is obvious to anyone who has watched the bystander video: Mike was unarmed and should not have been shot."

While the monetary cost of settlements with survivors or families is far from the most important negative outcome of police violence, the city does pay a big price for the improper use of force. In the city's fiscal 2020 budget, the Austin Police Department is funded at $441.7 million, or about 40% of the city's entire general fund (the part covered by taxpayers). That figure doesn't account for settlements paid in use-of-force cases; that money comes from the city's liability reserve fund, which takes in funds from all departments and pays out settlements of all kinds – car crashes, slip-and-fall injuries, and so on.

A 2016 paper published by Joanna C. Schwartz in the UCLA Law Review cites about $3.37 million in Austin police settlements from FY 2012 to FY 2014. The city itself estimates $8.95 million in settlements over police shootings since 2005, the largest of which, $3.25 million, was paid to the family of David Joseph. That total does not include other use-of-force incidents, such as the tasing of Quentin Perkins in 2018, which resulted in a $75,000 settlement, or the $425,000 settlement reached with Breaion King after she was slammed to the ground by an APD officer in 2016.

On top of the cost of settlements, the city incurs legal costs to defend its officers in civil suits, which it is required to do (the city cannot provide defense counsel for officers facing criminal charges). Some of these are handled by the city's lawyers and some by outside counsel, as is required by state law if in-house attorneys have conflicts or cannot take on the case due to their workload. In 2016, the city engaged local attorney Robert Icenhauer-Ramirez to represent former APD Officer Geoffrey Freeman, who killed Joseph. In that case, Council authorized the city to spend $316,000 on Freeman's defense, but the case was settled early and the city spent $75,000 on legal costs before a settlement was reached.

But the real toll of unjustified police violence falls on its victims and survivors, their families, and the broader community whose trust is eroded and whose right to public safety services is infringed. This is especially true for Black Austinites, who are subjected to police violence at disproportionate rates. In Austin, from 2008-2017, Black people were the victims or survivors of 31% of police shootings, at a time when the Black share of Austin's population never exceeded 10%.

The reality Black Austinites face is bleak, and the protests in Austin over the past four days are direct responses to inaction, or insufficient action, to change that reality. "People are seeing that a lot of the old gestures and nice words aren't going to be enough to satisfy an ongoing crisis on police brutality," Harris told us. "Not only is that still happening, but when it does, there is a lack of accountability.

"Unless people protest en masse, there is no justice. But it shouldn't require people to march and shut down freeways to get accountability."

Victoria Rossi contributed reporting to this piece.

Editor's note: This story has been updated since publication to correct Chris Harris' employer; he is director of the Criminal Justice Project at Texas Appleseed, a public interest justice center.

Got something to say? The Chronicle welcomes opinion pieces on any topic from the community. Submit yours now at austinchronicle.com/opinion.