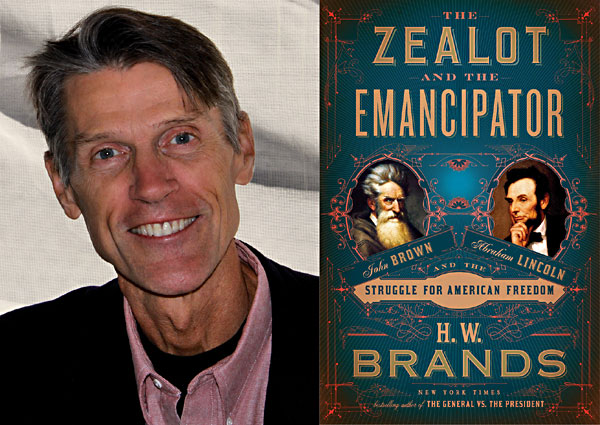

Book Review: The Zealot and the Emancipator by H.W. Brands

This history by the UT professor offers a new look at John Brown and Abraham Lincoln: side by side

Reviewed by Robert Faires, Fri., Dec. 25, 2020

When you see a book is called The Zealot and the Emancipator: John Brown, Abraham Lincoln, and the Struggle for American Freedom, you might reasonably expect it to be an Account of Great Men. The title puts history's stamp on its subjects, characterizing each in a single word aligned with the act for which he is remembered: Brown, the militant abolitionist who led an armed raid on Harpers Ferry; Lincoln, the Civil War president who freed enslaved Black people with the Emancipation Proclamation. Regarded as such, they're not so much men as figures of bronze and marble.

But you know that old saw regarding books and covers? Well, it applies here literally, for from the moment that H.W. Brands begins to tell their stories, interweaving the lives of Lincoln and Brown through their shared opposition to slavery, he presents them as complicated men of flesh and blood. The University of Texas history professor and prolific author opens two weeks after Brown's debacle of a raid, with the abolitionist in a jail cell, wounded and in pain, a husband writing to his wife to inform her that one of their sons died in his assault – one he'd never told her he was planning. Meanwhile, across what was then the country in Springfield, Ill., Lincoln is in his lawyer's office, dismayed by news of the raid, an aspiring politician of no small ambition worried about the impact it might have on his run for the presidency the following year. In this moment, both men appear vulnerable, their grand plans threatened.

These are the Lincoln and Brown that Brands wants us to know, the ones who don't have it all worked out. He takes us to their earliest days so we can see them as rather unpromising young men: Brown as the peripatetic farmer hopscotching across the country from one failed farm to another, Lincoln as the small-time attorney hankering after a career in Congress but sent back home after just one term. Both have had a hatred of slavery since youth, but in those days neither knew quite how to act on it. Brands leads us through their evolution into men of purpose and action, using alternating chapters to take us down their very different paths toward abolition, one by violent resistance and liberation, the other by political moderation and compromise. His approach also walks us through the slow boil of the country over the issue of slavery, from the Missouri Compromise of 1820 to the Compromise of 1850 to the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the Dred Scott decision that followed. With each event, divisions among Americans become more entrenched – Northerner against Southerner, free state against slave state – and the Union inches closer to war. The progression of this history, so artfully laid out by Brands, takes on the heat and inevitability of a classical tragedy, with Brown and Lincoln brothers in the same cause but driven to fight for it by conflicting means, each with its own terrible cost.

The "zealot" is the first to pay, and Brands provides a riveting account of the assault on Harpers Ferry, placing us at Brown's side for what feels like every minute of its 36 hours. In the end, the scheme to seize the federal arsenal, abscond with its weapons, and incite a sweeping slave revolt wound up, as one Republican then put it, "a wretched fiasco," with most of the raiders killed and Brown himself arrested, tried, and hanged. But even so, the act took hold in the public imagination of North and South, with Brown becoming an Old Testament prophet and holy warrior – a figure to inspire the former and incense the latter. That suggests how Brown, whose execution happens two-thirds of the way through the book, remains a presence even through Brands' shift to Lincoln and his canny maneuvering into the White House, his efforts to appease the South, his management of the war, and the move that makes him the "Emancipator."

Brands, following history, keeps his subjects apart, on parallel paths, but he gives prominent place to a third figure – a major figure of the day – whose path crossed Brown's and Lincoln's in significant ways: Frederick Douglass. The abolitionist, author, intellectual, and former slave knew both men and well enough to be the truth-teller to them. He was friendly with Brown for a dozen years and was actually invited to join Brown on the Harpers Ferry raid. Douglass told Brown to his face that it was a mad undertaking doomed to fail, a suicide mission. He publicly assailed Lincoln for his plodding efforts to free the enslaved, and Lincoln still sought out his counsel in private, where Douglass was no less candid about the president's halting efforts toward emancipation. The perspective that Douglass provides reinforces the sense of both Lincoln and Brown as men of vision, but limited vision, too much in the midst of what's happening to see where their actions would lead.

Perhaps that's why Brands gives Douglass the last word. He closes by quoting from a speech Douglass gave about Brown in 1881 and one he gave about Lincoln in 1876. Although both took place on commemorative occasions – the former on the establishment of a John Brown Professorship at Storer College in Harpers Ferry, the latter on the dedication of the Freedmen's Memorial Monument in Washington, D.C. – Douglass doesn't spare either man from criticism. He notes Brown's failure to achieve his goal of freeing enslaved Black people and leading "a liberating army into the mountains of Virginia," or even to escape from the raid alive. He characterizes Lincoln as "preeminently the white man's president" who was "willing to deny, postpone, and sacrifice the rights and humanity of the colored people to promote the welfare of the white people of this country." In both speeches, he notes his subject's faults and shortcomings before granting each man his accomplishments, his historic due: Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry was the blow that brought the long conflict of "words, votes, and compromises" to a close and began "the war that ended American slavery and made this a free republic"; Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation was "the achievement of a great and beneficent measure of liberty and progress." Ending in this way, with the assessment of someone who was personally acquainted with both men, their good and ill, and who was himself raised in bondage, chained by the very system that Brown and Lincoln detested and fought to destroy, Brands relieves the zealot and the emancipator of their iconic status and leaves them as men who made indelible marks upon their time, who changed the course of this country, and for all that were still men.